Spirit of the west

City Hall Watcher #197: Contributor Joy Connelly wonders if Toronto Council should learn a lesson on constituency work from Vancouver, while Matt projects voter turnout

Here we go — the home stretch. There are seven days until Toronto’s next municipal election.

This week, we’re looking westward as City Hall Watcher contributor Joy Connelly asks a darn good question: What if Toronto’s municipal government was more like Vancouver’s?

Specifically, what if our councillors were freed from the demands of constituency work and could focus more on city-wide issues?

Intriguing, right?

I’ve also analyzed advance voting numbers to estimate turnout for this election. It’s a prediction that’ll either make me look like a genius or a damned fool. High stakes!

A programming note: because I don’t think it makes a whole lot of sense to publish an issue on election day, next week’s issue will be delayed until AFTER the election. Expect some in-depth analysis of the results and the implications for the Council Scorecard in your inbox sometime after the results come in.

Since this is the last time we’ll talk before voting day, let’s recap. It’s been a busy campaign season. Here are some of the resources published in City Hall Watcher over the last few months:

This newsletter has also brought you thoughtful contributions on campaign issues from Erin Wotherspoon, Spencer Kelly and — in today’s issue — Joy Connelly.

One more plug: a reminder that I am on a panel this Wednesday talking about Strong Mayor Powers. You can attend in person or virtually.

— Matt Elliott

@GraphicMatt / graphicmatt@gmail.com / CityHallWatcher.com

Read this issue on the web / Browse the archives / Subscribe

Why are City Councillors our 311 fallback? Lessons from Vancouver’s municipal government

By Joy Connelly

This year, seven City Councillors decided not to run for another term, citing “the emotional toll,” “too many missed children’s bedtimes,” and the impossibility of one councillor “trying to meet the needs of 120,000 residents.”

Council renewal is not a bad thing. Given the enormous advantages of incumbency, some Councillors need to step back to allow new leaders to emerge. But if the demands of the job are so onerous that they threaten the well-being of Councillors and their families, something is wrong.

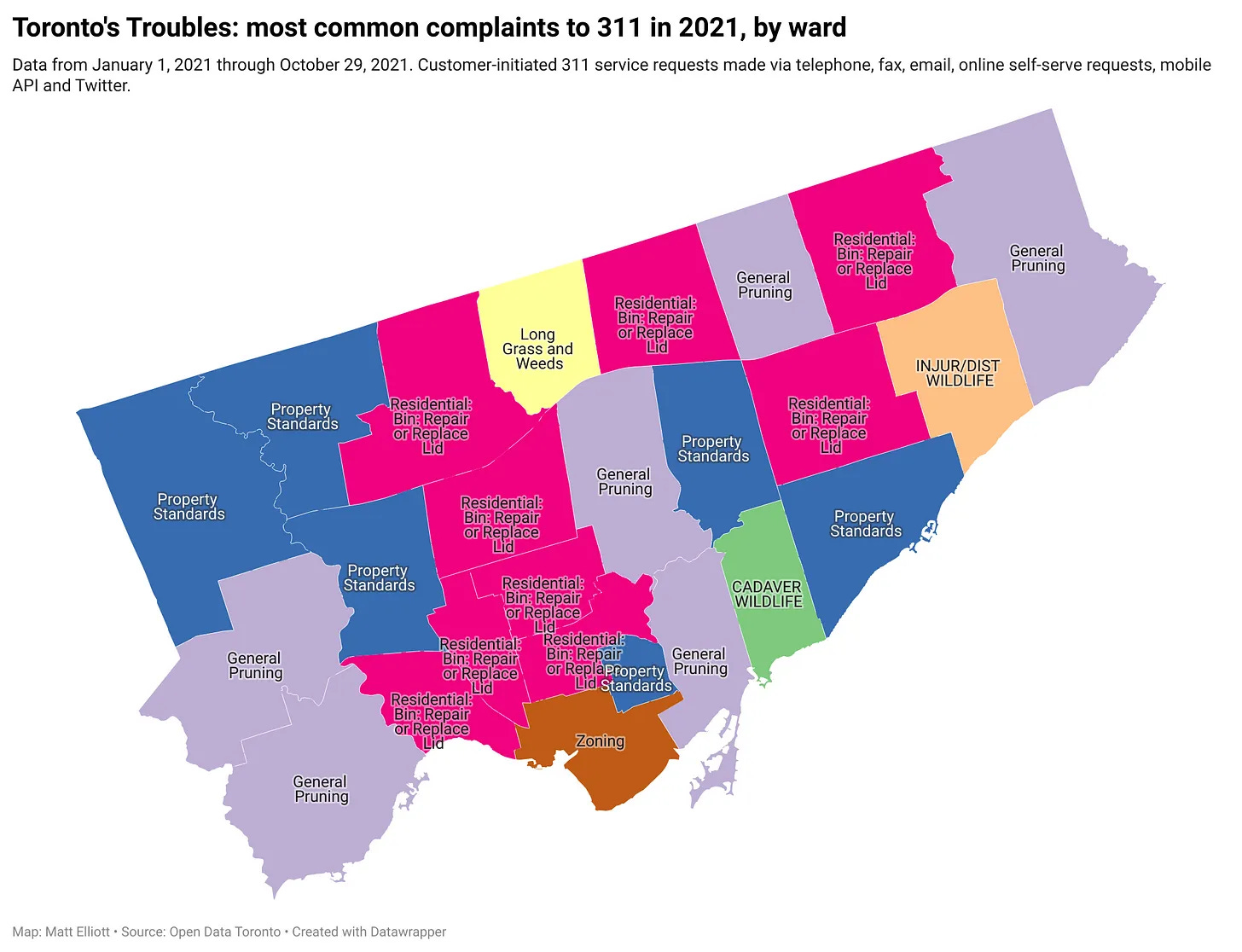

I believe that “something” is constituency work. Many Torontonians make their Councillor their first call whenever they have a question or complaint and expect them to take an active role whenever a new development or initiative is proposed for their neighbourhood.

It’s a task that is unequally divided.

The Ward 10 Councillor must respond to 67,930 households. In Ward 7, it’s 36,220.

This month there are 170 major active development applications in Ward 3. In Ward 24, there are 38.

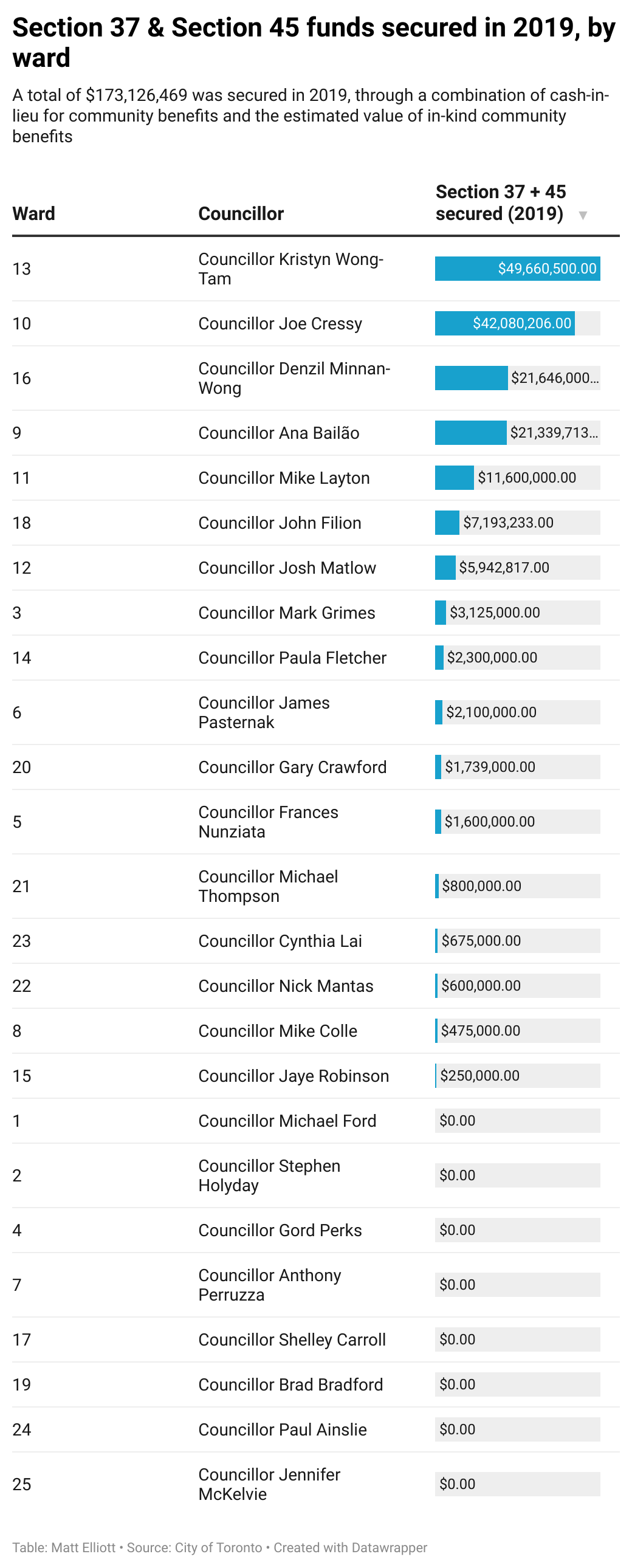

And if one looks at the value of Section 37 and 42 Community Benefits in 2019 – one indicator of the volume of complex development negotiations – the six busiest wards are those of six of the seven departing Councillors.

It’s also a system that leads to inequitable results. Thanks, at least in part, to my local Councillor, I don’t see garbage on my street, the roads are in good shape, and there are at least port-o-potties in the park year-round. That’s not the case in many other neighbourhoods.

How would Toronto function without local constituency work?

It might be helpful to look at Vancouver, where City Councillors do no constituency work whatsoever. That’s because Vancouver does not have a ward system. The Mayor, each of the ten members of City Council, a nine-member School Board and a seven-member Parks Board are elected at large.

Vancouver City Councillors do not have their own staff. They are not called upon to fix potholes, negotiate community benefits with developers, or host consultations with their constituents. These duties belong to City employees. And yet Vancouver residents arguably have greater opportunities than Torontonians to comment on every new municipal masterplan, rezoning or initiative.

Like Toronto, Vancouver has a 311 system that can be accessed by phone, online, or via the Van311 app, with a link to a contact list of City staff. This is where “pothole fixing” happens.

Unlike the City of Toronto, however, Vancouver’s website puts community engagement front and centre. Both the City of Vancouver homepage and its 311 page provide direct links to Vancouver’s Shape Your City page, where opportunities for input range from City-wide issues such as a Draft Capital Plan for Park Board Priorities to local initiatives like a single dog off-leash area.

If you’re a real civic keener, you can also join Talk Vancouver to participate in surveys as one of the City’s “community of trusted, local advisors.”

The Shape Your City site also offers all the information one could possibly need to comment intelligently on a rezoning or development application: a summary of the application (offered in ten languages), relevant plans and policies, maps, drawings, past and upcoming open houses, a backgrounder on the rezoning process, and phone and email contact information for both the proponent and the City. Comments can be made right on the page and are then combined with all written comments on the application in a public staff report to Council.

Does that mean all’s well in Vancouver?

Apparently not! The rout of the incumbent Council in Vancouver’s election last Saturday suggests voters are not happy. But if the platform of the newly elected Mayor and his ABC Vancouver party is any indication, neglected basic services are not the problem. Of the over 90 promises in their platform, only a few — more public drinking fountains, showers and washrooms, 100,000 new trees in under-served areas, and more pedestrian-controlled intersections — might fit into the “311” realm.

My own, admittedly anecdotal, knowledge of Vancouver’s 311 says the same. When I asked Vancouver friends, I heard, “311 is great,” “widely used,” and provides “instant service.”

I’m not sure Toronto residents would say the same about our 311 system. But perhaps that’s because it’s never been resourced as the way to address everyday problems. And perhaps some Councillors are ambivalent about losing their “go-to” role for constituents with problems. After all, Rob Ford rode his reputation for constituency work all the way to the Mayor’s office.

From local champions to city-wide leaders

I’m not suggesting that Toronto adopt an “at-large” Council. Vancouver has 24% of Toronto’s population and 18% of the land mass, so it’s easier for a city-wide Councillor to have a reasonable understanding of the issues in every part of the city.

But I do believe we need to shift the Councillor’s function from a hands-on role to a governance role, and from local champion to city-wide leader. The problems Toronto faces — housing affordability, poverty, aging infrastructure, climate change, inequity and, most importantly, inadequate funds to meet the city’s needs — require city-wide solutions.

And could we enable City staff to do what they are trained and hired to do? Toronto’s future depends, frankly, on investing taxes from rich neighbourhoods to support poor ones. But it’s not easy for Councillors in wards that are already rich in parks, transit, and thriving commercial streets to say “not our turn” when constituents ask for more. Staff have the tools to objectively determine where needs are greatest. City Council’s difficult job is to ensure they have the resources to meet those needs.

The hard question is, “Who will be the brave Councillors who challenge the ‘Call the Councillor’ default, and do the important work of making Toronto a great city not just for their own ward, but for all?”

Joy Connelly grew up in Vancouver but has lived and worked in Toronto’s affordable housing sector for almost 40 years. She sees this article as “musing out loud” and welcomes comments at joyconnelly@mac.com.

By the numbers

Total, all Councillor staff: 156 (as of October 12, 2022)

Median number of staff per Councillor: 7

Largest Councillor staff: 10 in Ward 7: Humber River-Black Creek

Smallest staff: 2 in Ward 1: Etobicoke North

Largest population growth, 2016 – 2021: 17.9% in Ward 10, Spadina Fort-York

Greatest loss: -4.1%, in Ward 23, Scarborough North

Greatest revenues from community benefits – an indicator of complex development negotiations