What the dickens is going on with transit construction costs?

City Hall Watcher #263: Guest Damien Moule on the sky-high cost of building subway infrastructure. Plus: a look at per-capita budgeting.

Hey there. This week’s City Hall Watcher features the return of the always noteworthy — and footnote-worthy — Damien Moule.

He’s read through the TTC’s capital plan and is trying to understand why transit projects in our city are ridiculously expensive. Why can Paris build and upgrade transit for a lot cheaper than we can? Is it something to do with all the baguettes?

Also, there is more transit news. I looked over the new TTC board meeting agenda and discovered — fittingly — that the cost of a major transit project is increasing.

Finally — and by request — I attempt to reverse-engineer a per-capita budget chart dating all the way back to 2016.

✨ This issue runs a little long. If it gets cut off in your email client, read it on the web.

— Matt Elliott

graphicmatt@gmail.com / CityHallWatcher.com

Read on the web / Archives / Subscribe

A Tale of Two Subways: why are Toronto’s transit construction costs so expensive?

By Damien Moule

You may have heard that it’s budget season in the City of Toronto. Like all the other people with a totally normal level of interest in the Capital Budget and reserve funds, I have been browsing through some of the thousands of pages of supporting documents in the proposed budget.

Every year, staff at the TTC present two main budget documents to the board of directors. The first is the proposed Operating Budget and 10-year Capital Budget. This is the document that makes its way into the City of Toronto’s annual budget. The budget document also includes a section on what it calls “unmet capital needs,” which are projects which are unfunded in the proposed capital budget but that the TTC recommends be completed within the next ten years.

The second document is the Capital Investment Plan, which looks at what the TTC considers its 15-year capital needs. This document is not part of the budget approved by Council, and 74% of the Capital Investment Plan is not funded. This possibly raises some metaphysical questions about the meaning of the words “investment plan.” But for our purposes, what this document represents is what the TTC thinks it will cost to keep up the state of good repair of the existing system over the next 15 years and fund all of the existing transit expansion projects that Council has requested to be studied.

Now, something in the Capital Investment Plan caught my eye. No, it’s not the jaw-dropping total value of $47.855 billion1, which nearly equals the total value of the City’s entire $50 billion 10-year Capital Budget on its own. No, it’s not that the value of the Capital Investment Plan has increased by $9.8 billion compared to last year’s plan. What caught my eye were the estimates of the costs of the projects to upgrade the Bloor-Danforth subway line.

These upgrades would add Automatic Train Control to the Bloor-Danforth line at an estimated cost of $867 million. The existing aging trains don’t support automatic control, and so there is $3.2 billion for the purchase of 80 new trains, 55 for Bloor-Danforth, and 25 for capacity expansion on the Yonge-University line. Finally, platform edge doors would be added to the Bloor-Danforth and Yonge-University lines at an estimated cost of $4.1 billion2.

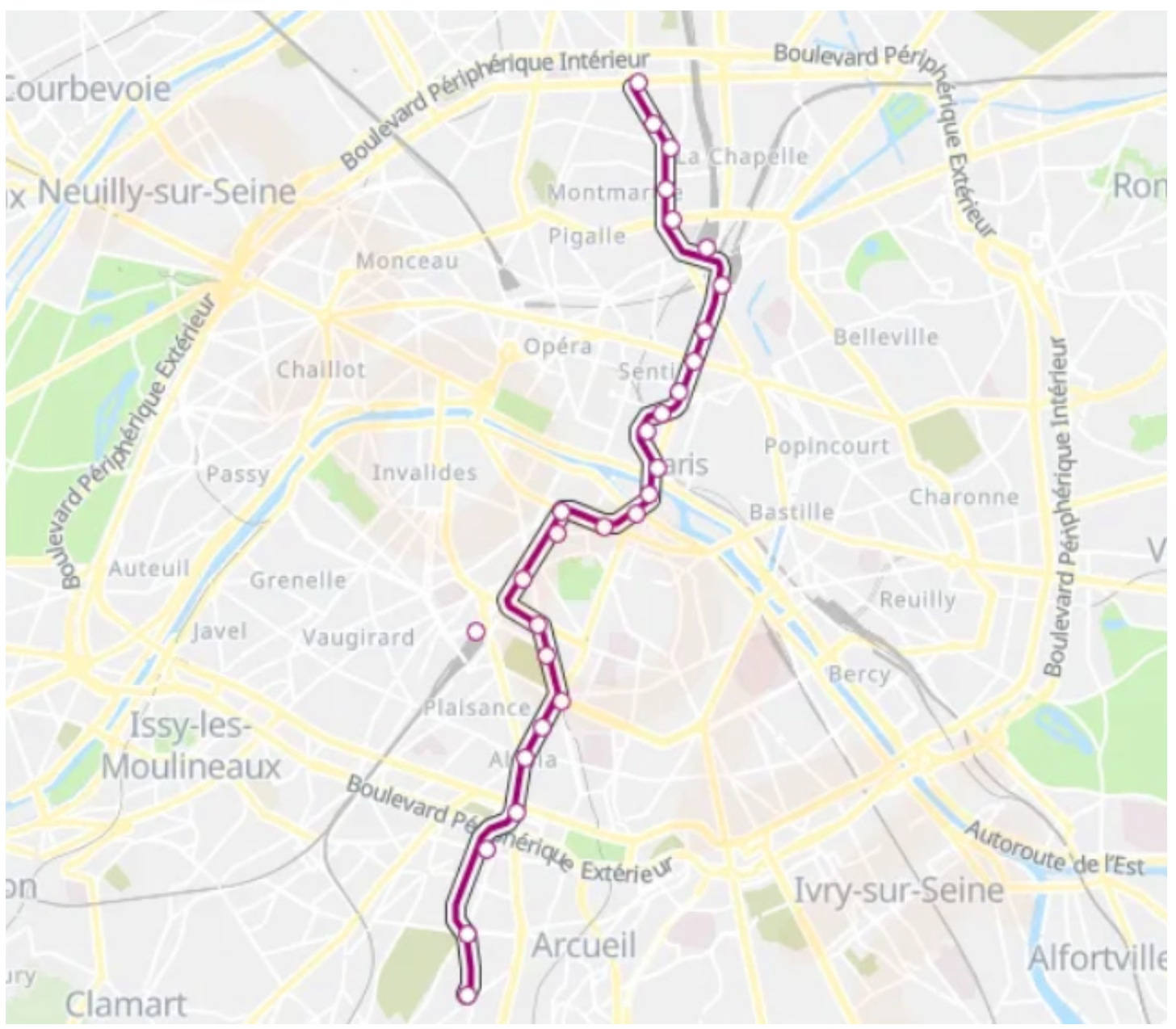

The reason these projects stood out to me3 is that I had coincidentally read about a very similar project which had just been completed for Line 4 of the Paris Metro. For reference, Line 4 is a rubber-tired metro line which starts at the northern boundary of Paris, then travels south through the centre of the city and under the river Seine before terminating in the southern suburb of Bagneux. It carries roughly 700,000 people on a typical weekday, which is slightly more than the Yonge-University Line in 2022, and much more than the Bloor-Danforth Line.

Starting in 2014, Automatic Train Control was added to Line 4, and the stations were upgraded to include platform edge doors4. At a press conference in November, the RATP and the IDFM (roughly analogous to the TTC and Metrolinx, respectively) announced the completion of the automation of Line 4, which included the complete upgrade of all stations at a total cost of €480 million ($712 million CAD5).To support automation of the line, some trains were transferred from other lines on the Metro. This was supplemented by the purchase of 20 new trains from Alstom (the company that bought Bombardier) in 2016 for a price of €163 million ($229 million CAD).

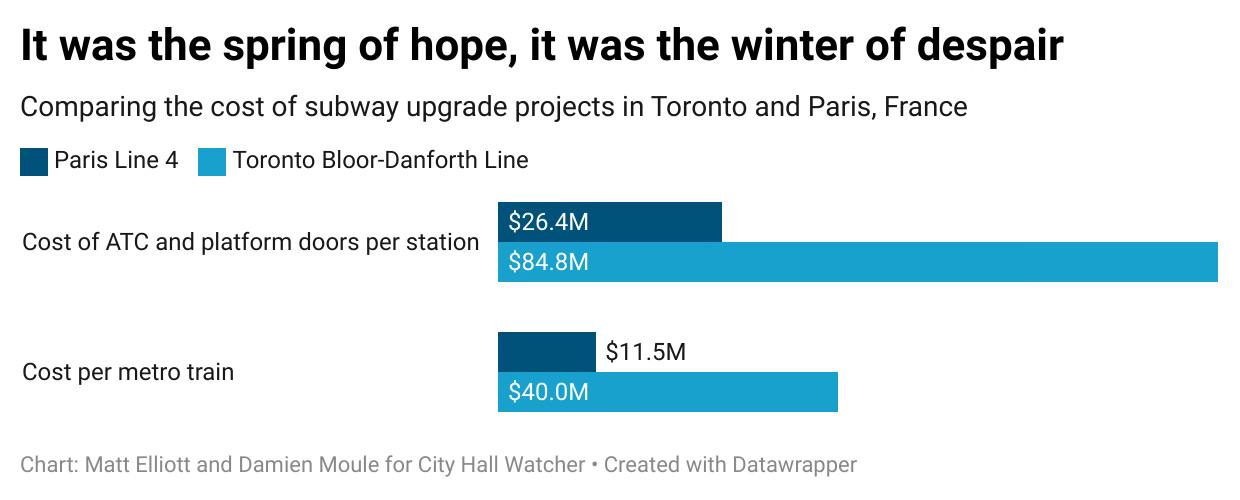

Now you may have already noticed that one of those costs is not like the other, but let’s just make this comparison a little clearer. The 27 stations6 of the Line 4 project were upgraded at a cost of around $26 million per station. Taking the Bloor-Danforth share of the platform edge door project7, and adding it to the cost to automate the line gives a total cost around $85 million per station. Similarly, the 20 new trains for Line 4 had a price of $11 million per train. The cost of the Bloor-Danforth trains is estimated at $40 million per train.

Let’s get a bunch of potential questions out of the way up front. Both lines use 6-car trains, though the Bloor-Danforth trains are longer at a little under 140 metres total with four doors per car, while the Line 4 trains are 90 metres long with three doors per car. The Bloor-Danforth trains are 3 metres wide compared to the 2.4 metres wide Line 4 trains. The Bloor-Danforth line will be 34 stations over 34 km following the extension to Scarborough. Line 4 is 29 stations over 14 km. Bloor-Danforth opened in 1966. Line 4 opened in 1908. Both lines will have been expanded in the middle of the automation project. I didn’t adjust any of the costs for inflation and I’m not sorry, since inflation can’t possibly account for the huge difference in costs.

I also want to note that I haven’t cherry-picked a particularly cheap example to compare against. The original estimate for the cost of Line 4 automation was €256 million, but the COVID-19 pandemic happened in the middle of the project, and it ended up 87% over budget and a year late. I’ve also compared against the TTC’s pre-construction estimates, which have a history of rising after the project is underway.

You may be tempted to start trying to dig into the specifics of the Bloor-Danforth projects to understand why its costs are so much more. What estimation method did they use? What are the labour rates? What inflation adjustments did they assume?

I urge you to resist that temptation. This isn’t a problem unique to any one project.

Have a look at any other project in the Capital Investment Plan and search for international comparisons. For example, the purchase of 2,935 low-emissions buses over 15 years at a cost of $4 billion. That’s $1.3 million per bus, which is roughly double the cost of recent purchases in Madrid, and triple a recent order in Taipei. There is a $3.6 billion dollar project in the Capital Investment Plan for a new maintenance and storage facility for the Bloor-Danforth line. The costs have gotten completely out of control all across the board.

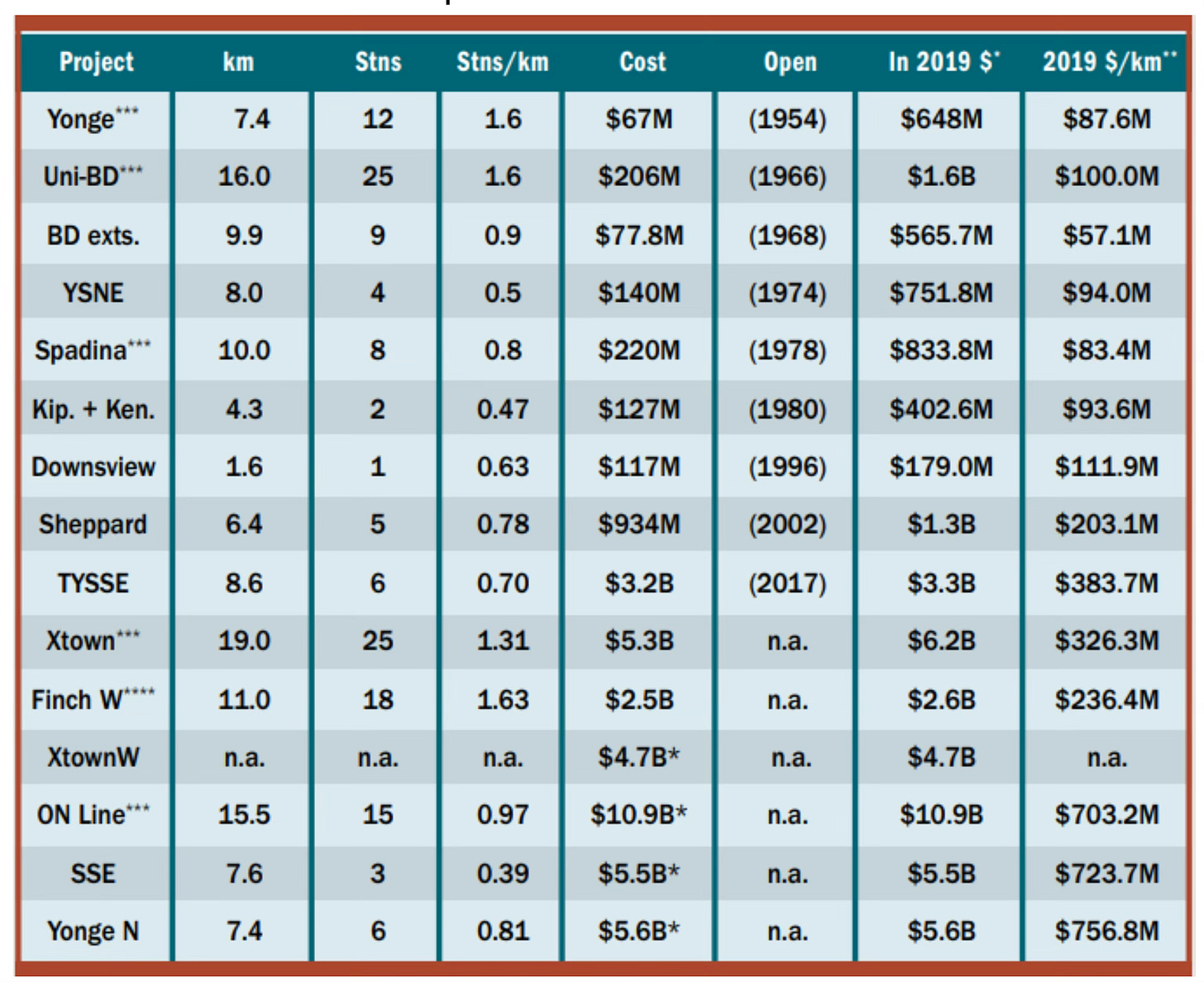

Now, it’s worth pointing out this isn’t just a TTC problem either. The project costs for Metrolinx are skyrocketing, too. The Ontario Line will cost significantly more per kilometre than the Yonge-University extension to Vaughan, despite having large portions above ground. And the Scarborough Subway Extension and Yonge North Subway Extension will be more expensive than that. This table from a 2020 report by Stephen Wickens for the Residential and Civil Construction Alliance of Ontario presents the clearest and most jarring summary of the increase in Toronto transit capital costs.

Nor is this just a Toronto problem. Transit costs are rising all across Canada. In Montreal, rising cost estimates doomed the REM de l’Est. Quebec City cancelled a tramway for the same reason. Vancouver, long the golden child for smart, cost-effective transit projects, has now seen the Broadway Extension cost rise to near Toronto levels.

In fact, this isn’t even a Canada-specific problem. As the Transit Costs Project from NYU’s Marron Institute has shown, transit costs have been increasing all across the English-speaking world. The United Kingdom, United States, New Zealand, and Australia have all been seeing increased costs in the 21st century.

What are some countries that have low transit costs, you ask, eager to confirm all your prior political beliefs are correct8? Turkey, Spain, South Korea, Italy. The highest? The U.S., U.K., Egypt, Hong Kong, Singapore. Whatever is happening, it has little to do with a country’s political economy. Building cheap transit projects is its own skill. It’s one we used to have, and have now lost.

The problem of rising transit costs in Toronto isn’t new, and it’s been covered before in both the Globe and Mail, as well as by Matt in the Star. It’s been highlighted by transit experts like Alon Levy, Marco Chitti, and Toronto’s own9 Reece Martin. TTC staff are aware of it, as I suspect are most councillors.

But it’s remarkable to me how little attention this issue gets. The discussion this budget season is all around a few hundred million dollars worth of property tax increases. The big infrastructure discussion in last year’s mayoral by-election was around which government should replace an elevated segment of the Gardiner. The Capital Investment Plan is an order of magnitude more expensive, and, if funded, it would add billions per year to the City’s budget.

One reason transit project cost increases might not get much attention is they scramble our normal transit conversations. For almost as long as I can remember, the debate around transit in Toronto has been about funding levels for the Operating Budget. This debate is straightforward: more funding would allow more vehicles to run more of the time, reducing wait times and crowding. More funding would allow for more maintenance staff. The political discussion is all around the “proper” funding levels for the TTC.

But rising transit capital costs don’t have anything to do with operations funding. When a new bus costs $1.3 million, it’s not because we haven’t been funding the TTC, and more or less funding won’t make the price come down. It’s just a separate problem that needs a different frame of mind.

Rising transit costs are also just all downside with no political advantage for anyone. If you were, hypothetically, a politician with an ambitious affordable housing platform, then rising transit costs are limiting the scale of what you can achieve. If you are a conservative politician trying to keep property taxes low, then rising costs just to keep up the state of good repair on the existing TTC network will force you into making unnecessary tough cuts. And no voter is going to want to hear that you can’t deliver on your platforms because we’ve just gotten worse at building and maintaining our transit system.

This is an enormous issue that needs solving, and fast. Dare I say a top five issue? Toronto is a growing city10, and the road network cannot grow any more11. The future of this city is transit12, and from this point on we need to be constantly adding to our transit network to ensure people can travel in a reasonable time.

We can’t afford to spend multiples of what other cities pay for the same project. We can’t afford to spend multiples of what we did 20 years ago just to keep the existing system from decaying13. The numbers we’re talking about here, totalling $47.9 billion, are too big for the City to manage. They’re too big for the Province to manage. We need to figure out what we’re doing wrong. We need to learn from other countries14 that do this better than us. And we need to do it now.

Damien Moule is an engineer, municipal policy nerd, Ward 10 resident, father, and occasional volunteer with More Neighbours Toronto. You can find him on Twitter (or X or something): @damienmoule