Don't blame bikes: an intersectional analysis of what really causes Toronto traffic

City Hall Watcher #309: Guest contributor Damien Moule returns with a look at what's really responsible for our traffic woes. It's not bike lanes. Plus: charting police budget increases, line by line

Hey there! I’m stepping back this week and handing over the bulk of this issue to Damien Moule. He’s looked into what really causes Toronto traffic. You may be surprised to learn it’s not bikes. Gasp!

It’s a fascinating analysis of how intersections change traffic flow. There are charts and footnotes. I think you’ll dig it.

For paid subscribers, this issue also includes a look at the line-by-line changes in the proposed 2025 Toronto police budget, laying out how much more the cops plan to spend on crime-fighting staples like animals, ammo and conferences.

🎁 ’Tis the season. If you’ve got a person in your life who loves nerdy analysis about municipal government, consider spoiling them with a gift subscription to City Hall Watcher.

✨ This issue runs a little long. If it gets cut off in your email client, read the rest on the web.

— Matt Elliott

graphicmatt@gmail.com / Archives / Subscribe

Bike Lanes, traffic lights, and confused common sense

By Damien Moule

Bill 212 has now been quickly adopted by Premier Doug Ford’s government. Among other (bad) things included in the Bill, it requires provincial approval to remove a car lane and add bike lanes, and threatens to remove parts of newly installed bike lanes on Bloor, University, and Yonge.

Many people are rightly upset about the indifference to the safety of people biking, the questionable legislative priorities of the premier, and the overruling of the elected government of the City of Toronto following a petition from a few well-connected Etobicoke business owners.

My reaction, however, has mostly been confusion. Deep confusion. Like down-is-up up-is-down levels of confusion.

Let me explain.

What common sense?

In his Toronto Star op-ed explaining the motivation for Bill 212, Minister of Transportation Prabmeet Sarkaria repeatedly invoked common sense as a justification for limiting and removing bike lanes. In his telling, it is common sense that the number of car lanes is limiting the capacity and speeds on our arterial roads.

This is the complete opposite of my common sense understanding of our roads. And this isn’t some elite downtown urbanist common sense. This is suburban car-centric common sense.

You see, my parents moved from Toronto to Aurora when I was an infant, and I grew up there. I learned to drive there. And the golden rule of driving in suburbia — one so ingrained that I doubt anyone would have ever needed to say it to me explicitly — is that you should always take the route with fewer traffic lights.

If you are driving to the movie theatre on the other side of town, you should take the road around the edge of town to get there. You definitely shouldn’t drive straight through the middle of town because you will hit red light after red light. That’s just common sense.

Traffic lights and capacity

In fact, that’s the entire point of traffic lights: to deliberately delay through traffic and reduce the capacity of the road to allow for safe crossing of the intersection. For two equally sized roads crossing each other, a traffic light will reduce the capacity of both roads by at least 50%, since the cars in each direction will be waiting at a red light at least half the time. More if there are turning signals.

Everyone understands this intuitively. The more traffic lights a road has, the more time a driver will spend stopped, and the lower the average speed of the road will be. The more traffic lights a road has, the more the capacity and speed of the road are limited by those traffic lights.

How can you tell if the capacity of a road is limited by traffic lights? The cars bunch up at a red light, with a large stretch of empty road behind them. When the light turns green, all the cars easily make it through the intersection during the green phase, and travel in that bunch up to the next red light.

Everyone who’s ever driven will be able to immediately picture the situation I’ve just described. It is the default pattern while driving, especially in the suburbs.

Find the bottleneck

How about University, Bloor, and Yonge? What is limiting car capacity and speed on those streets? Well, there certainly are a lot of traffic lights on them, even by Toronto standards. In the sections targeted for bike lane removal, the average distance between lights varies from every 159 metres on University to every 290 metres along Bloor.

At the speed limit of 40 km/h, travelling 159 metres takes about 15 seconds. A red light cycle typically lasts 60-90 seconds. Without a trunk full of lucky horseshoes, you will spend more time stopped at red lights than moving on University.

Moreover, the large number of lights on these streets is not an accident of history. Common sense would tell you to expect there to be lots of traffic lights along these streets.

Why? The subway.

Every subway station creates a lot of foot traffic in and out. The pedestrians need safe places to cross the street not just at the subway station, but for hundreds of metres in every direction. And subway stations are key focal points for the surface transit network. Almost every subway station will be fed by high-ridership buses or streetcars.

This presence of the subway also explains why everyone’s favourite quick fix, traffic light synchronization, won’t work for these streets. Synchronization is most effective when a major street is crossed by several minor streets. You can delay the smaller volumes at the minor streets to synchronize lights on the major street and make traffic more efficient.

When you have a major street intersecting other major streets, especially those with lots of transit vehicles, then synchronizing lights on one street means adding an equivalent delay to the people on the other street. On a street like University, which is crossed by four streetcar lines and two other major arterial roads, a rationalization of light timings to give equal priority to all travellers would likely slow down travel on University even further.

Capacity confusion

Okay, there are lots of lights on University, Yonge, and Bloor, but aren’t those roads still at capacity? No. And I have three ways to show this.

How would you know if the road was at capacity? It would be bumper-to-bumper traffic all through rush hour. Is this what we see on these roads?

I took these photos at the same intersection on University towards the end of morning rush hour on two random weekdays earlier this fall, but they could have been taken at any time of day on any day of the week.

This is a road whose bottleneck is traffic lights. Exactly like a suburban road. Cars bunch up at traffic lights, leaving large gaps of open road behind them.

But in case you don’t trust my photography, I have something more definitive. The car traffic on these roads has been going down for decades.

Subscribers to this newsletter will be familiar with Matt’s recurring feature of intersection inspection, where he uses Toronto intersection traffic count data for cars, pedestrians, and bikes to look at changes over decades. Today, we’re doing a scaled-back version, looking at just the north-south car traffic on University and Yonge and the east-west car traffic on Bloor.

I’ve plotted the average number of cars counted along those streets every 15 minutes by decade. Counts were taken over eight-hour non-continuous periods during the day.

As you can see, car traffic on all three of the road segments in the premier’s crosshairs peaked decades ago, and has been declining since well before bike lanes were added to any of them.

Last, let’s have a look at the data collected this summer as part of the Bloor St Complete Street extension. The project removed a lane of car traffic from Bloor, reduced the widths of the remaining lanes, added a cycle track, lowered the speed limit from 50 km/hr to 40 km/hr and made various adjustments to turn lanes.

After the installation, average speeds went down, and travel times went up, which is what the City intended, given the speed limit was lowered1 and the lane widths reduced. Notably though, the vehicle volumes changed by less than a percent. The removal of a lane of traffic in each direction and a reduction in average speed had no impact on vehicle volumes. That isn’t possible on a road that’s at capacity.

Putting it all together

Take these facts together: lots of traffic lights, large gaps between bunches of cars, declining car counts, and no decrease in vehicle volumes following a reduction in lanes, and I think it’s clear that these roads are not at capacity. They are slow and always will be because of the necessary traffic lights. But they are not at capacity.

That means that tearing out bike lanes to add car lanes will have no impact on car travel times. Not a small impact. No impact.

I really want to emphasize this. We shouldn’t be debating whether it’s worth slowing down cars on these streets to increase the safety of cyclists2. Or whether we should be taking out parking lanes instead of bike lanes.3 This misses the forest for the trees. The cars using University, Yonge, and Bloor will wait at the exact same lights for the exact same amount of time, and new lanes wouldn’t change that because the streets aren’t at capacity. Removing the bike lanes will be a pointless, wasteful act.

Before moving on, I want to address one feeling that I suspect is widespread. If these streets aren’t at capacity, then why does it feel like you’re stuck in traffic while driving on them? I think this is related to one of the most frustrating aspects of driving: sitting behind cars while the light is green, but you can’t move.

While acknowledging this is annoying, there are two things to remember. The first is that as long as you make it through the intersection during the green, it doesn’t matter when you get to accelerate. You will travel in the same bunch of cars regardless. The second is to recall suburban common sense: the only reason you are waiting to accelerate is the stop light. If you were travelling along at the speed limit behind the same car, it wouldn’t feel frustrating.

Toronto’s Traffic Troubles

I think the whole Bill 212 saga is part of a deeper failure to apply common sense when thinking about traffic in Toronto. You see, it’s not just these three streets whose speeds and capacities are limited by traffic lights. On most roads in Toronto4 traffic lights are the bottleneck.

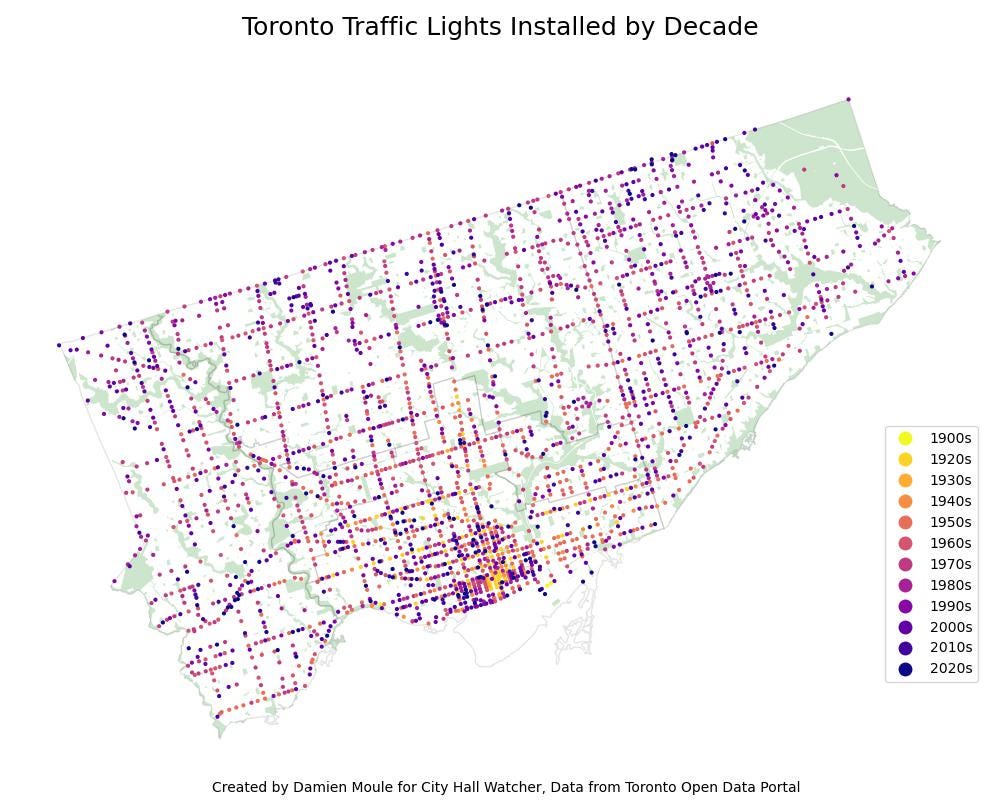

This is because the City has a lot of traffic lights. Like a kind of silly amount. And it has been getting more over time. Below I’ve used Toronto’s dataset on Traffic Control Devices to plot all the traffic lights in the city, along with the decade they were first added.

As you can see, while the majority of the lights were added during the post-war growth of Toronto’s suburbs, the City has not stopped adding them. And as the population grows, the number is likely to go up. Traffic lights will slowly but surely reduce the capacity of Toronto’s roads over time.

Why do we have so many? Because it’s the City’s default response to any and all traffic problems. Too many cars trying to cross at a side street? Add a traffic light. Is it unsafe for pedestrians to cross the street? Add a traffic light. Having trouble turning left? Add a traffic light.

But traffic lights are the most brute force means of traffic control. They make everyone come to a complete stop and wait so that each movement can happen in order, drastically reducing the capacity of the intersection in the process. They slow surface transit down to a crawl. They are also quite expensive.

So why does Toronto use them so much?5 I think it’s because of two ingrained assumptions. The first is that all intersections must allow cars to make every turn and cross them. If the volume of cars crossing a road at a side street is too high, the City will instinctively add a light.

Preventing the crossing using a median or blocking access to the side street would solve the problem just as well. It would direct the cars towards a major street that already has a light instead. This would be more efficient from a traffic flow perspective than adding a new light — and just as safe. This is one option among a suite of tools known as circulation planning. But I think it would be considered an affront to the idea that all cars must be able to go everywhere at every intersection. Better to stop everyone else for a minute instead.

The second assumption is that the only way to increase capacity is by adding lanes. In doing so, Toronto forgets the suburban common sense that traffic lights reduce capacity. If you can find a safe way to remove a traffic light, you add more capacity than by adding a lane to every direction.

These two assumptions create a feedback loop which leave the City’s roads an inefficient, frustrating mess. Adding lanes makes roads wider, which means they take more time to walk, bike, or drive across. This makes them less safe to cross6, and of course the cars must be able to drive through every side street, and so a traffic light is required. Adding traffic lights reduces the capacity of the road, eventually requiring more lanes to fit the same number of cars.

Multiple lanes in each direction also make it less practical to use the best technology for preserving intersection capacity: the roundabout. Roundabouts prevent the complete stoppage of entire lanes, and so have much higher throughput than traffic lights. They would be perfect for much of suburban Toronto, which already has large spaces for intersections. But they work best on roads with one lane in each direction.

Getting away from these two assumptions could make our roads much better. There are cities that do exactly that. They make wise trade-offs to sacrifice direct car access to every street in exchange for higher average speeds7 along major thoroughfares. They create high-capacity but compact roads with few stop lights, fewer but better intersections, and few entrances.

They manage to achieve higher average speed and lower congestion than arterial roads in Toronto, while achieving better safety for drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians alike. They finish well ahead of Toronto in the TomTom Traffic Index8.

They are Copenhagen, Stockholm, and Amsterdam9. Despite their reputations for cycling, these cities also think far more clearly than Toronto about car traffic. Amsterdam has a network of priority roads for cars which are designed to move traffic along efficiently and steadily at moderate speed. Go explore these roads on street view, pay attention to the traffic lights, the number of car lanes, and, yes, the separated bike lanes alongside them.

They know what efficient and safe car travel means far better than we do. They know that bike lanes keep slower-moving bicycle traffic out of the way of cars just as much as they protect cyclists. They know that high-speed car traffic can’t happen in the same place as high pedestrian traffic. They would never pick University, or Bloor, or Yonge as roads for car priority because they know it would be self-defeating. They know that to give everyone priority on every road is to give no one priority.

We should be learning from these cities that manage traffic better than us. After all, that’s just common sense.

Damien Moule is an engineer, municipal policy nerd, Ward 10 resident, father, and member of More Neighbours Toronto. You can find him on Bluesky at damienmoule.bsky.social.

Charted: Toronto’s growing police budget

I covered the basics of the 2025 budget proposal coming before the police board this week in Friday’s bonus issue. But thanks to a timely Open Data release, we can also do some line-by-line analysis, comparing the approved 2024 police budget with the proposed 2025 spending plan.

Here’s where spending is set to increase the most.